This paper provides insights into sustainable urban regeneration of historic city districts in Beijing as an alternative for the tabula-rasa towers that sprout up everywhere in contemporary urban outskirts. At the base of the research lies the resilient ecological system as a leading metaphor for creating sustainable living environments in which a resilient urban ecology forms a balanced dwelling habitat.

Problem Statement

Following this ‘Block Attack’ statement, I have further specified the problem framework for this paper and divided into three parts:

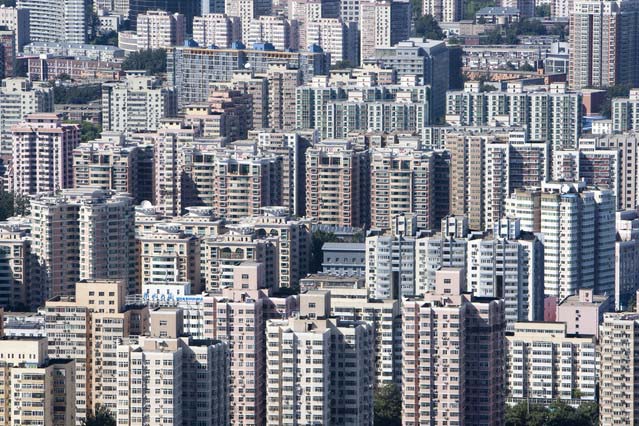

1.1 Contemporary Urbanization

Firstly, the general problem is defined by the context of contemporary urban China in which the process of rapid urbanization threatens traditional city patterns. The globalization of architectural discourse since the industrial revolution of standardized mechanization led to a singular modern ideology. Especially after the 2nd WW, when it was Philip Johnson who declared an ‘International Style’ in architecture at the MoMa in New York and from which buildings all over the world tried to adhere to a shared ‘international attire’. Within this light of generic international definition, dynamic vernacular city structures have gradually been replaced by static, planned settlements. Within these new settlements, either as a redevelopment of existing patterns, as new town additions to existing settlements or as new towns, the typology of the tower, or skyscraper, in particular has lacked a comprehensive argument to justify its global installment. In a country like China especially, that has a history of low-rise communities formed around a courtyard living typology, connected by bustling streets and alleyways, one might ask: “Why have we locked ourselves into mono-functional towers?”

1.2 Social Structure in Human Settlements

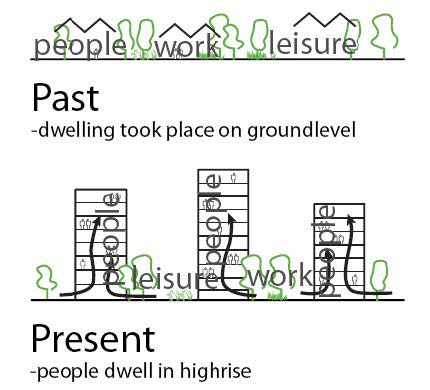

Secondly, not only does this ‘phallic typology’ not relate to an existing locality, it also opposes local social structures and the dwelling nature of people at large. The detached, vertically oriented towers therefore result in a detached vertically oriented living environment in which random people are stacked into shelves of apartments. Dwelling is pushed up into closed high-rises because of scarcity of land while leisure, work and service facilities are spread out into various podium levels or are highly concentrated amongst shopping areas, hubs and so forth. This is an undesirable development, as people originally are more accustomed to a more horizontal way of living, in which interaction and community sense are stimulated.

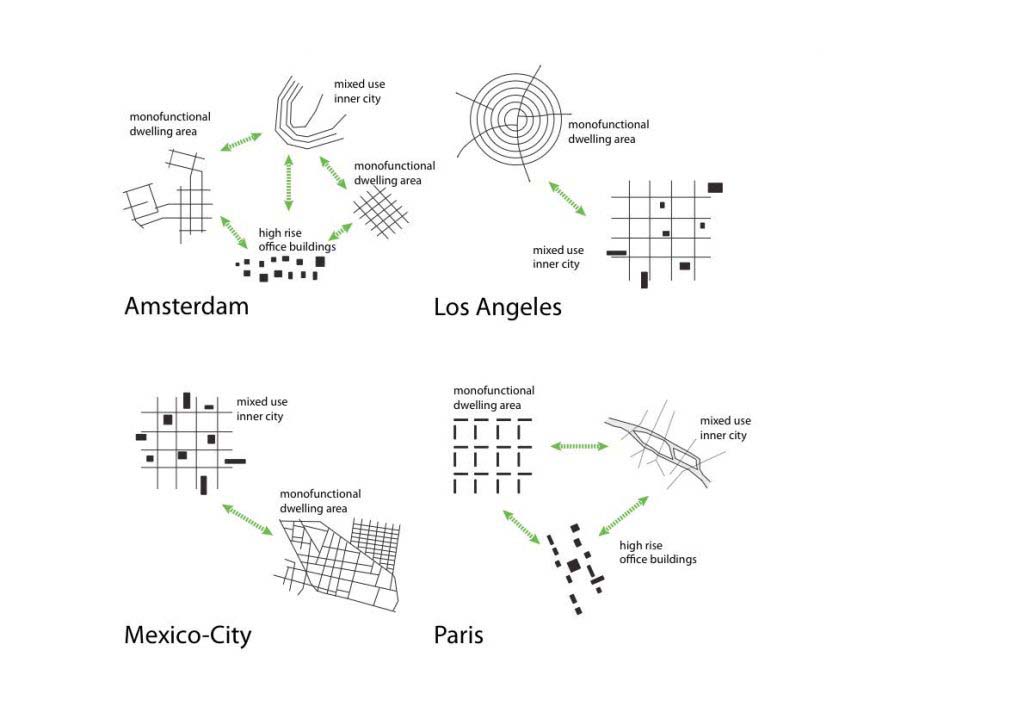

1.3 Segregated Cities

Thirdly, this segregation goes beyond the building typology, and also exists at the level of the modern city. According to Koolhaas for instance, this separation between city and architecture can “only lead to insidious proliferation or metastasis”. As a result of the application of functional segregation in modern town-planning, all over the world vast dwelling areas in modern urban agglomerations, in which the largest share of build program consists of housing, are now planned as autonomous islands without identity or ‘raison d’être’. Can we regenerate the mixed program and urban identity?

By using an overall generic framework to embed the chosen specific context, this research paper aims to distill a specific implementation proposal and to simultaneously generate conclusions that can be applied to similar generic context affecting other specific local areas.

Theoretical Framework: ‘Balanced Ecology’

Architecture and City Planning are both concerned with the planning/designing of complex systems in which a variety of stakeholders is destined to live together in a designated habitat. The leading concept for creating this habitat is derived from a comparative analysis on natural eco systems and can be framed as a ‘balanced ecology’. The ideal intervention then regards a design proposal that sees the community operating as a diverse eco-system: dynamic, complex and resilient.

As briefly stated in the introduction, I would argue that in the course of this ‘sustainable regeneration’, we can learn from disciplines that concern ecological systems, especially those related to the comprehensive regeneration of eco-systems. This metaphor is relevant for various reasons concerning ‘regeneration’, ‘locality’, the ‘mixed use environment’ and a balance between various types of residents.

First of all, environmental researchers, biologists and ecologists in this field already have a good track record for the regeneration of natural habitats at places where they where once destroyed, which could thus be a good reference for understanding how to understand and bring back the local characteristics in a new, genuine system, in which the system becomes resilient and adepts and transforms over time to accommodate further changes.

Secondly, this metaphor allows us to address the topic of ‘locality’ as various regions on micro and macro scale hold distinct habitats. Though the constituents of these areas are shared all over the world, these established habitats have historically always been locally specified and further influenced by in- and outside forces that change over time. (geological patterns, local climate, species, human interventions, etc)

Thirdly, for an understanding of the stakeholders that make up a balanced system, we look at the benefits of a ‘poly cultural habitat’ in which various species with distinct roles (pioneers, perennial, long term, i.e. mixed use vernacular cities) create a self sustaining growth, in contrast to ‘mono cultural farming methods’ in which large areas of single species are planned and up-kept artificially (such as mono-functional residential communities in the outskirts of Beijing).

Overall, as a general theoretical framework, this provides a background that supports the arguments for a shift towards an integrated sustainable urban planning method, as a tool to establish comprehensive regeneration of existing city fabrics. The three main components will be described below:

2.2.1 Regenerating Habitats

Over time, traditional urban fabrics all over the world had to adapt to changing forms of habitation, new uses, new types of infrastructure demanded new urban patterns, or some even had to recover from complete destruction. Similarly, existing natural habitats have to deal with various outside pressures that thus force a change of system, in which sometimes natural or ‘man-made’ disasters completely wipe out or severely damage the original ecologies (forest fires, or deforestations for instance), just like certain urban fabrics were destroyed (war/ bombings in Rotterdam or Tokyo, or earthquakes and fires for instance).

Unfortunately, while attempts in regenerating, or bringing back original natural ecosystems, while accommodating the required contemporary changes, have been very successful in many places (Rhine river in Europe, Willie Smits in Indonesia, etc), the regenerating of traditional city fabrics have not seen such great examples yet. For, all though cities like Rotterdam and Tokyo certainly have revived into vibrant new centers and adapted well to new requirements of density, infrastructure and so forth, their original characteristics (typological locality), and traditional social structures (a horizontal society) have not been restored.

2.2.2 Locality

Secondly, this paper attempts to describe a form of urban development that is rooted in the local characteristics of place. As a result of better living conditions, the availability of economic potential and the richness in facilities we see people flocking to the urban areas. The density of opportunities is attractive. But as we are more free to settle, we are also more free to leave again. (New) cities have become similar in experience, but still depend on specific regional attachment of people within their vicinity. A stable density is key in successful development of new urban areas and the question is no longer ‘how can we attract?’, but ‘how can we sustain?’ the people within our boundaries. In the past ten years basically every city has developed two or three focal points that should lead to an improved, independent and ‘unique’ identity. A whole new profession has risen, ‘City Branding’ in which teams of architects, graphic designers, strategy consultants and media communicators try to provide solutions for creating the ‘Instant Perfect City’. Something out of nothing. ‘Better City, Better Life’. And here we have a problem. We see crazy efforts in trying to be different, to outsmart the global.

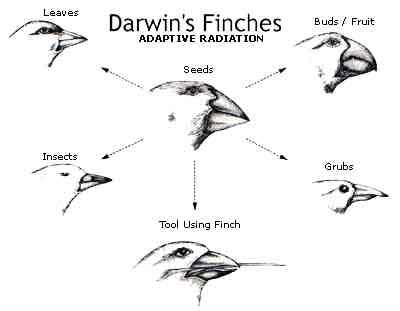

Again, here we can learn from the natural metaphor, as each ecological system is naturally embedded within a certain local specificity. The famous biologist Charles Darwin has been a pioneer in understanding the local characteristics of these natural eco-systems and the way how they transform towards their characteristics, as explained through the Finch-diagram in which the same species adept to the specificities of particular island habitats.

Thus, when we talk about how to create local identity, rather then a generic solution and it is based upon the understanding of the regional urban framework and specific Beijing urban typologies that create particular local identities for our issues. I doing so, the creation of an embedded local identity revolts against contemporary urban developments in which we only see ‘more of the same superficial, arrogant, shiny images of premature urban infusion’. Beijing does not need any more glittery high rise egotistical urban nothingness, but should rather use its cultural constituents as a base for developing a resilient city fabric.

2.2.3 Poly-culture Shock

The poly cultural shock strikes two ways, first of all, in a successful regeneration intervention, one must use a poly-cultural planning method, to avoid too much focus on a single species and one must realize, once an eco system is destroyed, it can’t be regained by an instant, replacement of the individual species. The same is valid for human constructions and social communities. We thus propose a successional, timebased approach to its re-growth, executed over a trajectory of years. Spatially organizing a dialogue between, and redefinition of, old and new values, ideas and ego’s in architectural teaching.

The result will be a community operating as a diverse eco-system, dynamic, complex and persistent. It settles down within a very few years and undergoes continuous growth, change and innovation that feeds and enriches itself and its environment. The hutongs themselves becomes a living organism. And in its visual appearance and operating performances it reflects the changing forces that structure ideas about the relationship between architecture, science, economy, politics and culture.

James Drake and Stuart Pimm of the University of Tennessee study what it takes to arrive at an assembly of species that remain in equilibrium (…). They begin by adding species in various combinations and then letting them work out who will survive and in what ratio. Eventually, without intervention, the community shakes down into something that is both complex and persistent – order for free. ‘But we don’t get order immediately, says Pimm, ‘We get it after a long period of adding species to communities and watching them come in, displace other species and go extinct in their return.’

In other words, ‘having a history is what makes a community last’.

Conclusion

In relation to the comment above, this paper has tried to provides some suggestions that aide a practical implementation for a sustainable alternative with low-rise-high-density re-generation of historic city fabric in Beijing.

By using proven examples from natural ecologies as a base for understanding city regeneration, it is possible to understand the complexity of city development through a simplified model of relationships. This cross-disciplinary approach allows for a crossbreeding of ideas that enrich traditional mono-functional, generic city patterns through a creation of smaller, more human-scaled, horizontally oriented habitats based upon local typologies.

References

Benyus, J, Biomimicry, 2002, Harper Perennial

Friedman, TL, The World is Flat – A brief history of the 21st century, 2007

Geus, de M, Definitions of Locality, 2010

Geus, de M, Er’tong Urban Oasis, 2011

Geus, de M, et al., Hutong Ecology, 2013

Koolhaas, R, Content, 2004

Koolhaas, R &B Mau, B, SMLXL, 1995, Monacelli Press

Maas, W, et al., The Vertical Village, 2012, NAi Publishers

Mumford, Lewis, ‘What is a City?’, 1937, Architectural Record

ecology, globalization, regeneration, skyscraper, sustainability