From Public to Civic Spaces. On the development of collaborative community design in China.

This is an article that reviews the development of collaborative community design in China. It aims to interpret the evolution in local co-design methodologies, the planning and process tools used in this and it’s recent history in relation to the cultural framework and planning directives.

The starting point is how in the past decade in China the conception on developing communities has changed. From a process embedded in a public-private duality in which responsibilities were top-down implemented, merely focused on ‘producing space’, toward a renewed concept on civic spatial processes that opens up new directions for urban planning interventions, based on collaborative community design that also considers a component of spatial negotiation through time. No longer merely about the pure production of space, but changing toward a long-term process of growing communities.

This text was originally published in Volume Magazine #53: Civic Space.

See here.

For clarity to readers that might not be very familiar with the local situation in China, nor the evolution of planning policies, this paper consists of a three-tiered main body with concrete examples from Beijing as supportive cases to this change in conception. In addition, the article starts with an introduction on the changes regarding this conception of planning, and mention briefly how China went from ‘everything is public space, no privacy’ to a ‘public space erosion’, end then the three cases illustrate the change in conception regarding the production of civic space and its spatial negotiation through time.

Introduction

Since the fall of the Qing dynasty, in 1911, successive waves of modern forces have changed the pattern of urban development in China. These have severely changed and pressured the traditional urban patterns. Taking Beijing as an example, we can describe the traditional urban pattern during the imperial times before 1911, as a fully private family environment in enclosed courtyards, 院子 (yuanzi). With the establishing of modern China in 1949, this changed to residential district planning with a fully public lifestyle with no privacy and shared washrooms, in communist live/work units, 大院 (dayuan). After the reform and opening up period in 1980’s, this shifted toward a capitalist development model, controlled by private developers, with housing estates, gated communities and private apartments, that fuel large parts of GDP development. Since 1949, China went from ‘everything is public space, with no privacy’ to a severe erosion of public space because of the radical influx of private development.

And it’s fascinating to witness that a kind of new planning is happening in the decade following the Beijing Olympics, a development that is not top down only, and not strictly divided between public (government) and private (developers). The Fifth Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) put forward building a social governance pattern characterized by multiple subjects, equality-based consultation, and co-governance, in which the urban community would become the core in promoting social construction (Zhang, 2014). This new planning directive focuses on a change in process, and a change in development. This central government directive has since been implemented in lower level planning incentives, to encourage collaborative design processes in urban design, and experiments are being implemented that are not intended to give an immediate fixed result, but based on a model of spatial negotiation through time.

Thus, rather than (only) defining the intended outcome, e.g. to produce space for living, there is a strong emphasis on the participatory design process with various parties involved. We could define this as a move from public to civic space, not with a black/white division of tasks between us and them, but with a collective civic responsibility.

Three areas of Beijing discussed in the paper.

This article discusses three areas in Beijing alongside this change in development, all being developed in the mixed-use inner city historic core, from the past decade. The three cases are all situated in Beijing, since the change in development from public/private is exemplary for the wider change in China. The first area, Qianmen, is a highly controversial development, regenerated alongside the city-wide efforts that marked the 2008 Beijing Olympics. It is one of the prime examples of eroded public space, due to private development principles, and almost single handedly marks the tipping point in the change in recent policy. The second shows a pioneering pilot project right across the first example, called Dashilar. The third area is a more matured and integral implementation of this civic design process, which started roughly 2 years ago, and is still fully under way around the White Pagoda Temple, Baitasi.

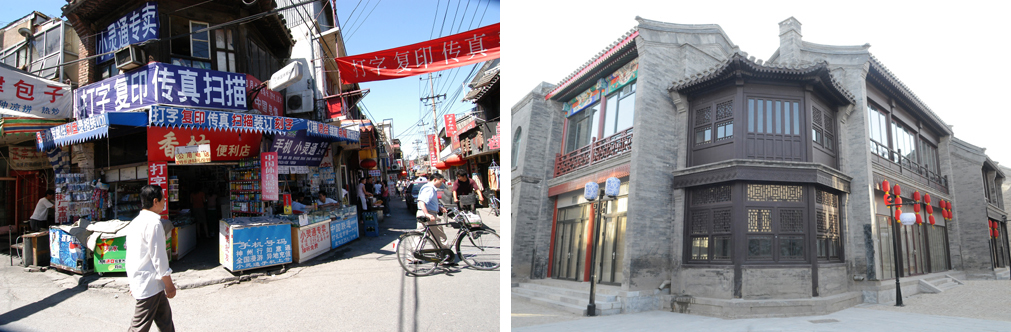

Eroded Public Space; commercial development of Qianmen

In the above-mentioned residential district planning and housing estate planning, though applying a different process, the purpose and output of the planning methods are both directed to the same objective: producing space. In the case of Qianmen, the production of space to maximize the return on investment of the over-priced land with very limited height restrictions. In preparation of the 2008 Beijing Olympics, many projects where top-down conceived and executed without any design of community in mind, the Qianmen area southeast of the Tian’an’men square is a good example of this. For centuries long a very public, lively area just outside the inner city wal, but still within the lmperial city. The plan however was purely capital driven, privatized and full of prestige, without consideration of the ‘spatial negotiation through time’ nor any ‘co-design methodologies’.

The result, a historic wallpaper facade over a cleaned up series of concrete supposed-to-be shopping facilities. According to leading state-owned newspapers of the time a ‘“substantial improvement in appearance”, at face value. But, unfortunately not lasting. Behind the glittery facade make-over there was little substance left.

The area, it turned out to be a painful embarrassment, right in the center of the city, under the eyes of the emperor. Similar to other developments around China, thousands of residents were relocated for the redevelopment in Qianmen. But, in part given its high-profile location, the project was publicly criticized and heavily debated, not only amongst preservationists and intellectuals, but this critiques were coming from local Beijing residents as well, many of whom have connections to the tight-knit community.

This all happened after the implementation of the plans, in the aftermath of the Olympics and the public outcry against the redevelopment at Qianmen prompted respected local academics and preservationists to put a stop to similar type of top-down plans in other areas around Beijing. In response the Beijing government stopped all major construction projects that were planned for the old city area, and issued Suggestions to Strongly Promote Cultural Development in the Capital’s Core Areas, issued on November 4th 2010.

Local Response, early pilots. The Dashilar Project.

Thus, a stop on the bottom down, demo/rebuild type of historic redevelopment was immediately enforced. At the same time though, a large number of built residential areas were still in urgent need of renovation and qualitative improvement. Parallel to this rising awareness, community planning, rather than mere space production, had seen an upsurge throughout China, taking the long-term underdevelopment of social aspects and the development of a social living environment as its core. Compared with the former two types of planning, the focus of community planning begins to shift to social development, which aims to achieve such social objectives, such as equality, a healthy environment, reduction of poverty, etc.

Here, space is neither a single nor a final planning goal; it is ultimately aimed at the development of a society through the process of planning, and through the process of community design.

In parallel, largely as a response to the Qianmen project, and the change in Beijing’s planning policy, many local scholars and practicing architects had been writing about this problem in those years, and the central government has subsequently adopted their suggestion towards a ‘bottom-up’, ‘community based planning’, that was first tested in the Dashilar area, on the opposite side of the Qianmen district; on the south-west corner of Tian’an’men Square.

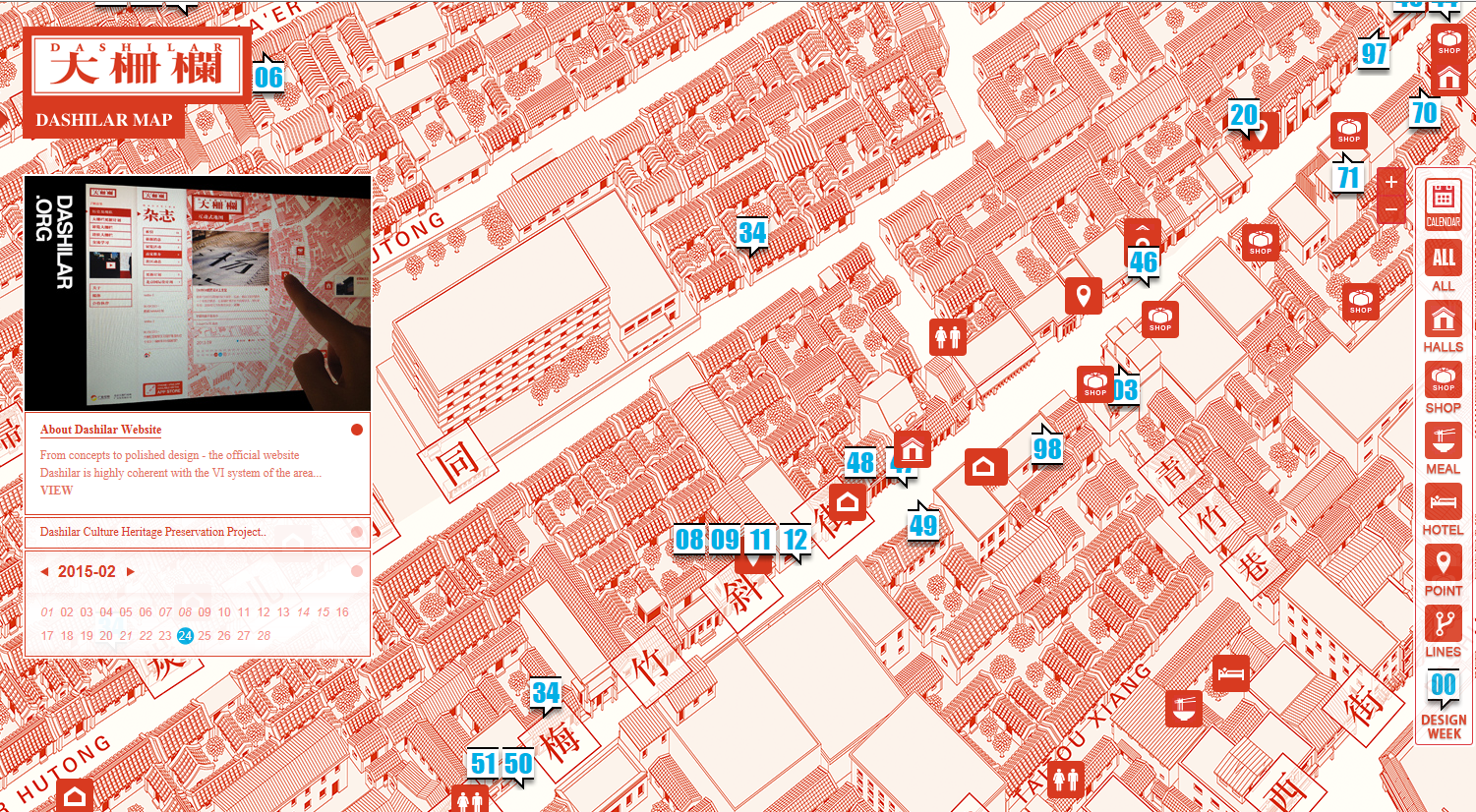

An interactive online map, displaying the integrated urbanism approach.

A multi-disciplinary research was also started at this time, called Meta Hutongs, to map and analyse the Dashilar area, supported by the local developer, and with support of external sources, such as the Graham Foundation, that combined students from three local universities and various professionals to investigate potential for interventions, and to assess the needs of the community. As an experiment in urban redevelopment, the overall Dashilar Project adopted a more time-based, civic approach. Various stakeholders worked together, a state-owned local design institute, BIAD was placed in charge of monitoring the development, a professor from Tsinghua University’s School of Architecture oversaw the masterplanning, and a new development company was formed that had its office in the area.

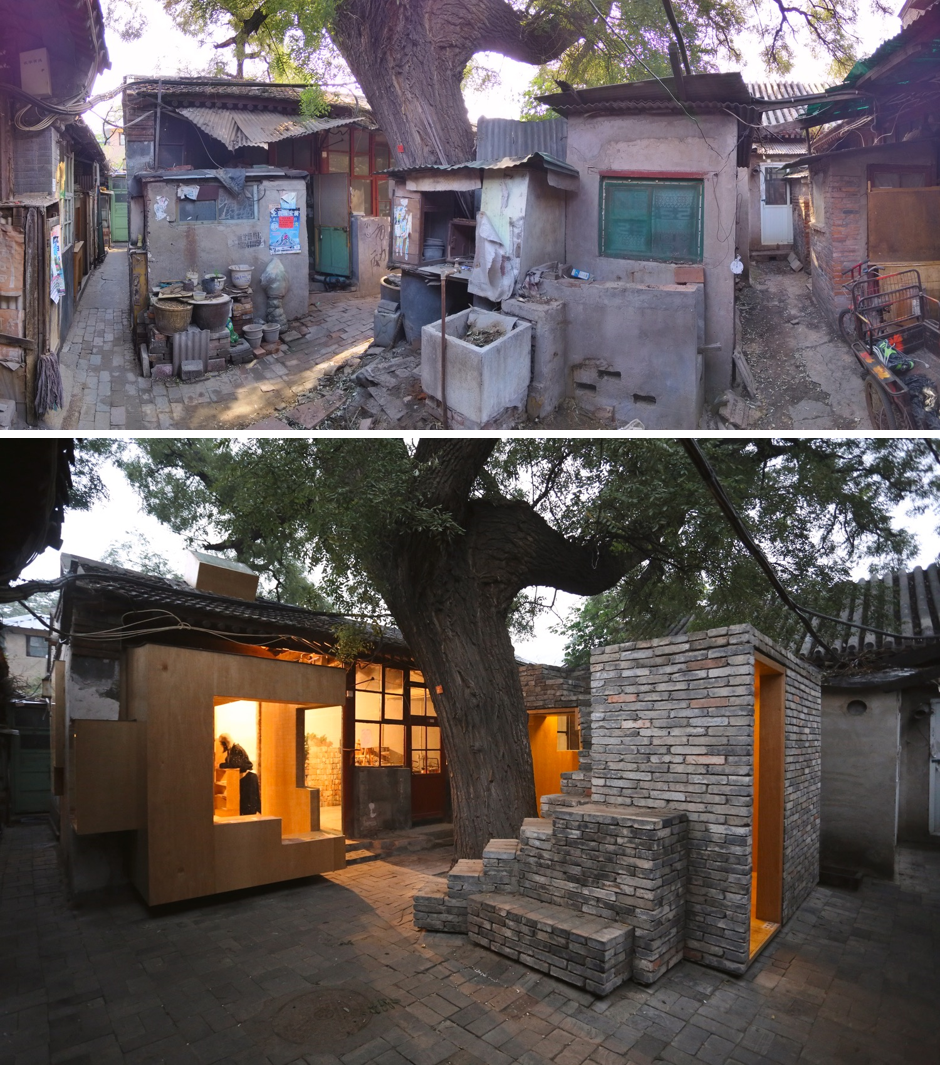

Dashilar pilot project, community library. Before (top) and after (bottom).

The local community was involved, and a curated spatial approach was developed, in which all the acquired dilapidated (public) houses remained untouched regardless their conditions and were rented to carefully selected new owners, who fit the needs and prospects of the area, and were willing to be blended into hutong life.

The participative design process instigated here also led to several pilot-projects, implemented over the course of several years, with program that would benefit the community at large. The most famous architectural example of this would be Zhang Ke’s Children’s Library and Art Center, that won the 2016 Aga Khan Award for Architecture.

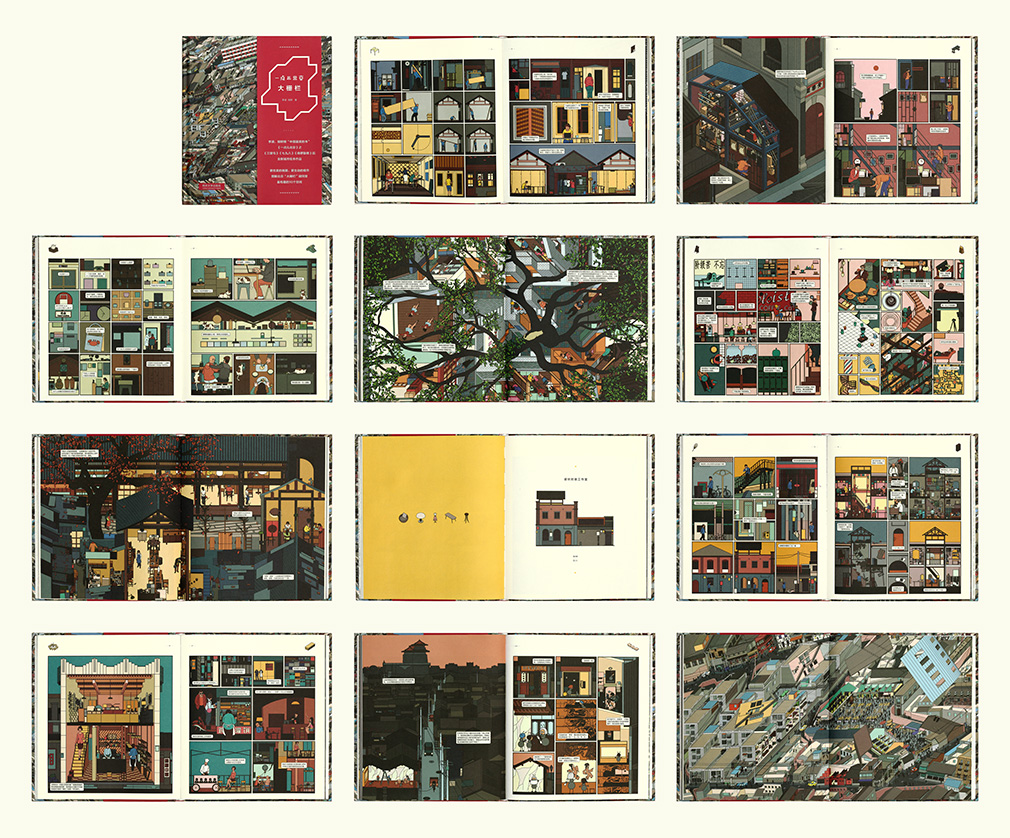

A Little Bit of Beijing · Dashilar, showing the renovated courtyard with the Community Library and Art Center.

In addition, the transformation of the entire area was well communicated to the general public, through the area being one of the key areas for the Beijing Design Week, but also through bottom-up initiatives, such as the now popular comic-style book A Little Bit of Beijing · Dashilar by Drawing Architecture Studio with ten cases selected from the Dashilar Project, including hutong renovation projects by architects, unfamiliar religious space, unique restaurants and cafes, and creative studios located in the hutongs. The authors try tell the diverse story of collaborative community design, including the successes and difficulties, hoping to bring more awareness to the issue of urban redevelopment.

A Little Bit of Beijing · Dashilar

Formalized model: Baitasi, around the White Pagoda Temple.

Thirdly, after the successful trial and assessment of the Dashilar efforts and its pilot-projects, the Beijing municipal government redirected the model to be formalized, and applied in a more central and sensitive Beijing city district, in the area surrounding the White Pagoda Temple: Baitasi. Baitasi is a cultural and historical preservation zone inside the former Imperial City, a traditional hutong area covering 37 hectares, located just across Beijing’s Financial Street District.

Learning from Dashilar, this time a comprehensive formal framework was set up where a developer, master planner, the local governments, residents, architects, academics and students work together, called “Baitasi Remade”.

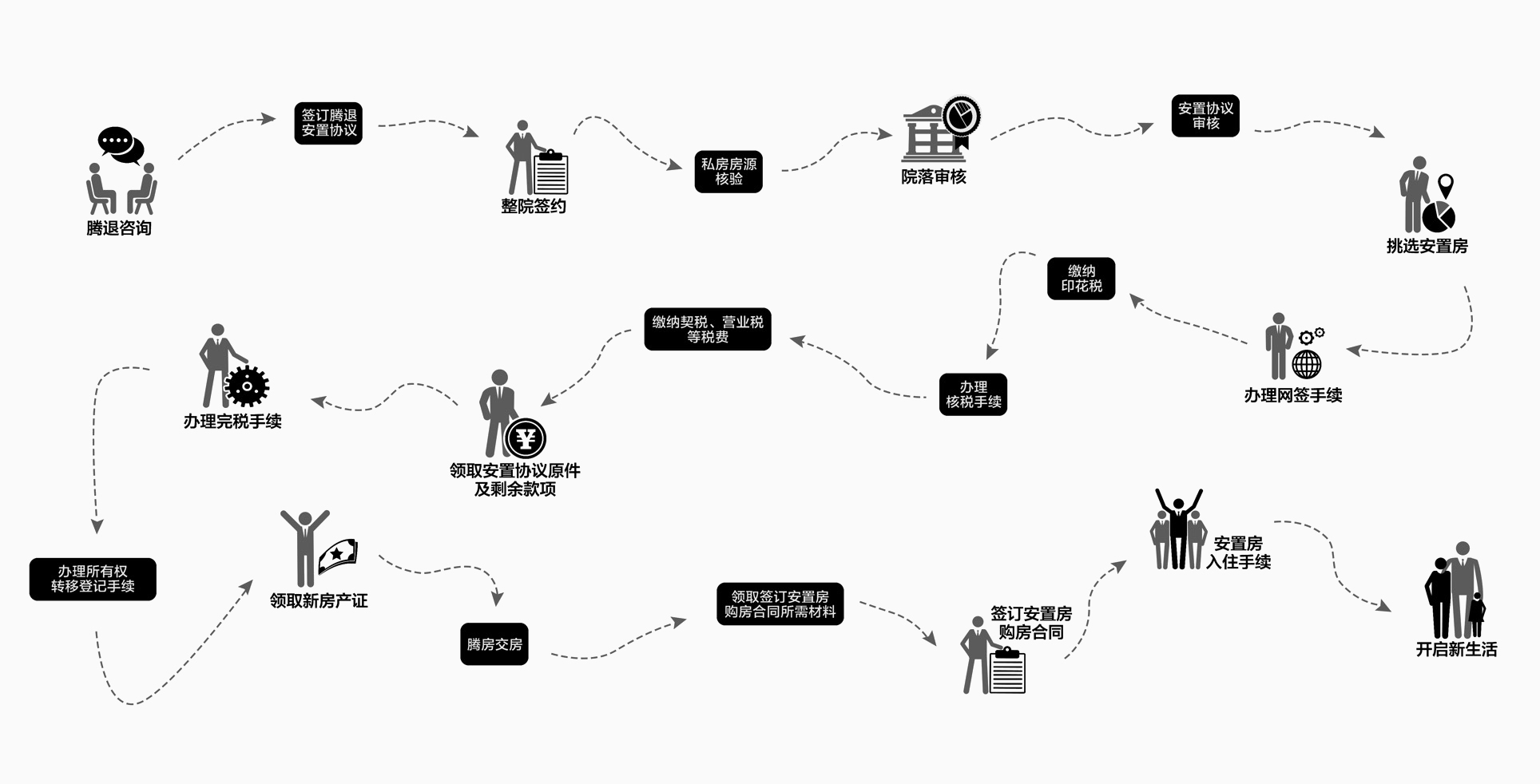

Stakeholder and process diagram

A big difference with the Dashilar project, is that the main objective for the Baitasi area is not a mere gentrification with new actors, but foremost a social process in which local residents and facilities are improved first, before new, outside stakeholders are being brought in. In addition, given new developments such as the rise of Air-bnb, Uber (in China: Didi), shared bike systems and so forth, a special program was conceived to fit the rise of the shared economy. The official incentive is “to establish a new model for local residents with the aid of public participation and model enterprises and government leadership”, and the general approach follows four main directives:

- Continuous movement of resident to areas of low residential densities

- Improvement of public environment

- Introduction of social catalysts

- Design and creation of communities

A partnership was formed between the Beijing Huarong Jinying Investment & Development Company, the local government, and a team of urban designers and architects from Tsinghua University’s School of Architecture. The combination of academic, market-driven and government parties means a broad process can be facilitated, in which research can be implemented almost real-time. An academic journal, WA/ World Architecture facilitated a series of public forums and competitions for young architects to bring in fresh ideas from outside.

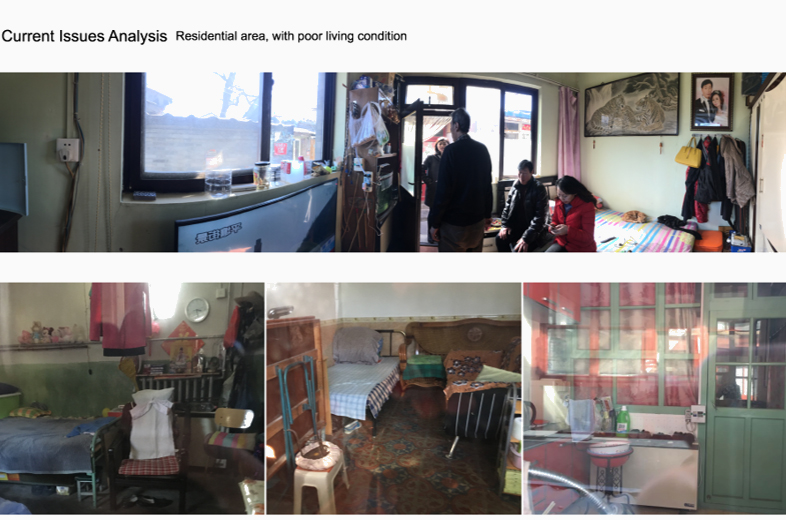

Residential analysis by architecture students from Tsinghua University

The Baitasi Remade project aims to take an investigative, participatory approach, working with local residents to assess processes of transformation and the effect they have on individuals’, institutions’, corporate and governmental co-participation larger framework of stakeholders. Project wise, on an architectural, social level, there are two realized pilots worth mentioning. The first one is a model house, aiming to facilitate the movement of people to areas of low residential density, developed in close collaboration with the original residents of the plot.

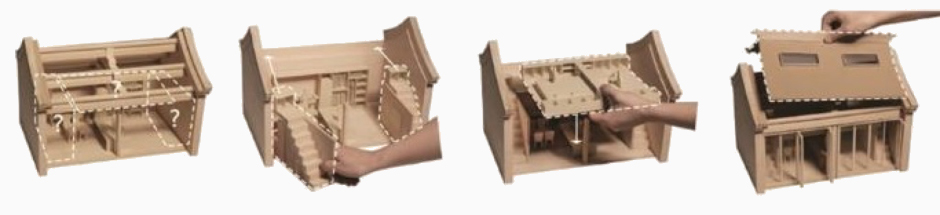

Physical model to facilitate discussion with local residents

The renovated ‘model house’, with prefab bathroom unit

The three original rooms housed two families, with a series of illegal additions that included a kitchen, bathroom, etc. In this project the illegal additions were removed, instead a compact, multifunctional storage solution was created inside, a second loft-floor added, and a prefab toilet united located in the yard. The result is two family units and one central ‘shared room’, that can be used to receive guests or for leisure activities.

To assess the practicality and effectiveness of the design intent, one of the units is now occupied by the project-manager from the developer. The other unit is occupied on a two-week rotational base for families in the area that like to try and see if they would like to have help to adopt this approach in their own homes, a post-occupancy evaluation of a broader scenario that is still to come.

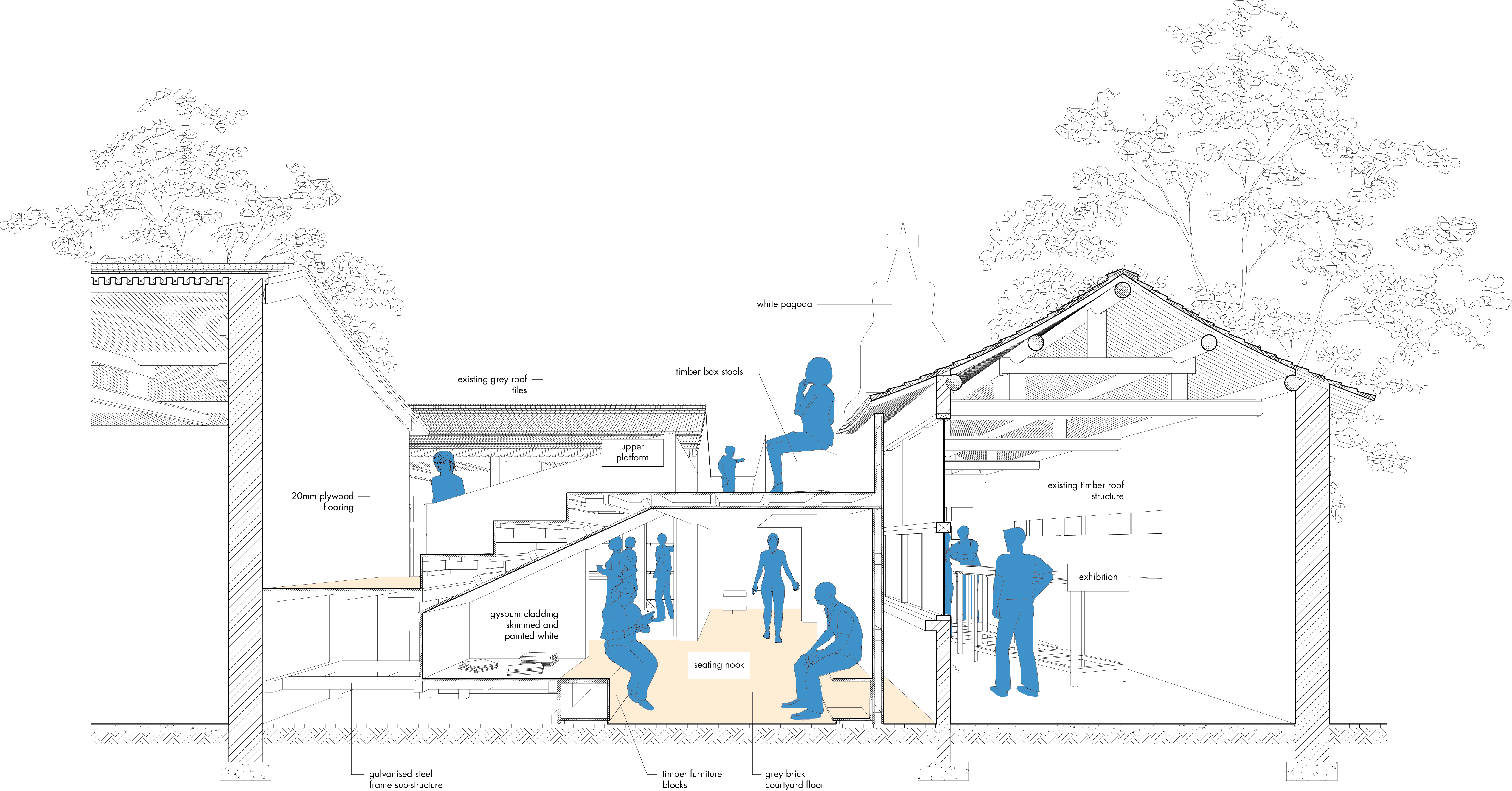

The Baitasi ‘sharing courtyard’, conceived by students from Tsinghua University.

The second example focuses on the improvement of the public environment, and is the result of an 8-week long urban design studio at Tsinghua University, called Sharing Cities.

Again, as part of directly testing the research, the local government allocated a dilapidated courtyard for to regenerate, as a test case for the student’s ideas. The design was inspired by the opportunity to bring a new perspective to the traditional hutong experience and allow people to explore and utilize the courtyard in three dimensions, including quiet corners, a skywalk and small amphitheater, and is implemented as a usable addition to the neighborhood, not as an abstract stand-alone installation. The new structure creates a very direct connection with the renovated courtyard house, and opens up never-before seen perspectives.

Perspective Section

Conclusion: Effects and Applications.

For the sake of a fair comparison, and considering the limited space in this article, the examples mentioned here are pre-dominantly concerning the redevelopment of historic areas, however, since the Qianmen debate, this process of community based development has extrapolated itself to other urban typologies, areas and cities, such as in the redevelopment of former soviet-style housing communities, or in the redevelopment of business districts, currently going on in the CBD in Shenzhen for instance.

Concluding, however, first a critical note. Though these examples are of quite successful implementations, there is in many areas still a disconnect between the planning directives, the intentions of the community-based design and the actual spatial output. The current emphasis on community planning is on the one hand a product of a general dissatisfaction with previous models, but also a result of an evolving society and the current state of the urban social development. After a period of standard blue-print driven top-down development models, the increasingly complex urban and social problems, call for “interdisciplinary and cross-sectoral integrity”.

Planners, architects and developers are increasingly aware that it is not only about the technical abilities of spatial planning and practice anymore, but that in the process it is now also required to develop skills of social negotiation and mobilization.

In this way, through the integration of top-down and bottom-up forces, the physical environment, cultural atmosphere, and quality of life of the community can be integrally improved. Because, as Winy Maas mentioned in a recent interview on this topic, “in the end it all relates to the durability, or the long duree of a project, and that’s what is also needed, it’s not about the building, it’s the in between.” This lasting effect of community based design, will certainly be a topic to keep reflecting upon while more cases and long-term studies become available in the near future.

Bibliography

K. Zhang, ‘A Study on Social Governance Under the Condition of Diversification’, Journal of Renmin University of China, no. 2, 2014, pp. 2–13.

Jiayan Liu and Xiangyu Deng, ‘Community Planning Based on Socio-Spatial Production: Explorations in ‘New Qinghe Experiment’, in City Planning Review, no 11, 2016, pp. 9-14.

Martijn de Geus, ‘Winy Maas and the Evolutionary City, Everything is Urbanism’, in World Architecture, no 7, 2018, pp. 100-105.

Web

Adam Mayer, ‘Experience Contrasts redevelopment of Beijing’s historic Qianmen Neighbor’, 2011. https://www.smartcitiesdive.com/exsustainablecitiescollective/experience-contrasts-redevelopment-beijing-s-historicqianmen-neighbor/59936/, accessed on 2018-06-15.

See: BHJCP, ‘The Beijing Cultural Heritage ProtectionCenter’,

http://en.bjchp.org

Tianran Xu, ‘Gulou to get small museum instead of ‘Time Cultural City’, 2010.

http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/599067.shtml

Other

‘Qianmen before and after its renovation’, China Daily, 13 May 2011.

http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/regional/2011-05/13/content_12508907.htm