Some may find it surprising that for a profession purposed with studying, designing and creating spaces, there is very little research into the spaces and buildings within which architects are educated. This is not to say that architecture schools have been designed without regard for the education being received within their walls. In fact there are countless examples of architecture schools which have been designed to specifically reflect and support the architectural ideologies of the school. This paper selects individual cases of schools from around the world and illustrates how the typologies and interior arrangement of architectural school buildings can be found to be reflected in the type of architectural education being taught at the time.

A concise overview of typologies

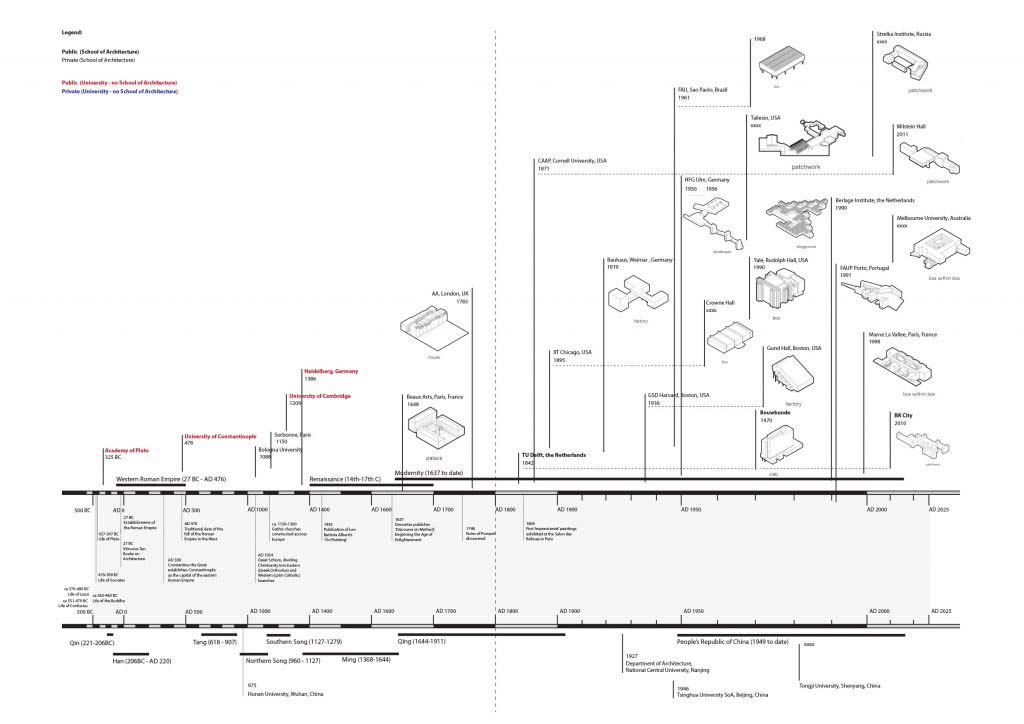

Following Donald Schon (1971), who states that society is in a continuing process of transformation, and the learning systems respond to changes associated with this transformation, the review is grouped into four distinct periods, in which a prevailing architectural pedagogy resulted from a broader social-cultural framework that was translated into a type of architecture and/or architectural learning system. We identified four such frameworks and periods: the Renaissance, Industrial Revolution, Post 1960’s and Post 1990’s. In the accompanying

timeline this overview is displayed against the social-cultural context in a graphic timeline, with simplified uniform images of each school’s building.

The founding of architecture schools – A timeline

1. Renaissance

In the seventeenth century, the national government of France undertook for the first time to foster architecture as one of the fine arts by supporting schools for the education of artists. Formerly, the arts had shared with other trades those educational facilities provided by the corporations or guilds under the system of apprenticeships carried on in the workshops or homes of the master craftsmen themselves.

“With the establishment of formal architecture schools, there was only one model of education that emerged in response to the value system of the time and the needs of the government“.

– Ashraf Salama

The time was the Renaissance, and the education model was called ‘Beaux-Arts’. According to Omer Akin (1983), the Ecole Des Beaux Arts emerged from a system of government which sponsored the academic institutions and established as an educational program as opposed to a vocational program. Collins (1966) points out that the beaux-arts system in France, far from being characteristically and traditionally French, is essentially Italian. This is understandable, as it was the time of rebirth of classical values originating from the Greek and Roman Empire, and this reference to Italy as the source for architectural education was also expressed in more contemporary references through the architecture itself.

Ecole Des Beaux Arts – Palais D’etudes

The school of architecture at the Ecole Des Beaux Arts was housed in a purposefully designed structure called ‘palais d’etudes’. The building was designed by Félix Duban who modelled it after an Italian Renaissance Palace designed by Bramante, The Palazzo della Cancelleria in Rome. The building was designed as a sort of gallery of objects, a Museum of Studies as written above the entrance door, to present castings of architectural patterns, copies of antiques and award-winning works of students. In the original Duban building, this gallery was in an open courtyard, it was covered later, in which students could observe and draw these copies. The Beaux-arts system was long the dominant style of education, and the buildings represented the architectural values clearly as a palace for studying exemplary projects.

Various other schools around the world, first in Europe, later around the late 19th century also in the United States, were started with this ideology and followed similar building typologies.

2. Industrial Revolution

Following the first period, architectural learning then adapted as social-cultural values changed in response to technological changes stemming from the Industrial Revolution. All structures and processes in society followed ideas of standardisation and factory-like spaces emerged in which new materials enabled light, open and flexible structures. Out of this revolution, only one alternative to the Beaux-Arts developed that embodied the changed value systems, the Bauhaus in Germany. In the words of Walter Gropius, designer of the Bauhaus school in Weimar:

“the New Architecture throws open its walls like curtains to admit a plenitude of fresh air, daylight and sunshine. Instead of anchoring buildings ponderously into the ground with massive foundations, it poises them lightly, yet firmly, upon the face of the earth; and bodies itself forth, not in stylistic imitation or ornamental frippery, but in those simple and sharply modelled designs in which every part merges naturally into the comprehensive volume of the whole.”

Bauhaus School in Weimar – Walter Gropius

Following the particular approach was not only limited to Europe though, as some of the key architects of this period moved to the United States during the times of the two World Wars and brought the modern Bauhaus ideas to the rest of the world. For instance with Mies van der Rohe’s Crown Hall for the school of architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago, which followed the open, light and airy characteristics of Gropius’ Bauhaus. Mies called the Crown Hall a ‘universal space’, because its design permits change in the function of the building while the architecture focuses on the permanence of the building’s surroundings. Upon its opening, Mies van der Rohe declared it “the clearest structure we have done, the best to express our philosophy”.

Crowne Hall at IIT – Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

In South America, heavily influenced by the modern Western architecture, the concept of ‘universal space’ was also adhered to in the design of the ‘Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism’ in Sao Paolo, Brazil. Here he principle design of the school was, according to the architects, based on the idea of generating spatial continuity. Therefore, its six levels are linked by a system of ramps in an attempt to give the feeling of a single plane and favour continuous routes, increasing the degree of coexistence and interaction among those who use it.There are no entrance doors, stairs or small spaces, the intention being the generation of a space in where you can perform any activity that you need to.

FAU in Sao Paolo

3. Post 1960’s

The technological advancements stemming from the Industrial Revolution were put to use after the two World Wars following a time of rapid rebuilding and standardisation of building processes. It then took until the (late) 1960’s that social values had changed again in such a way as to enforce a radical paradigm shift in architecture, defined by rich diversification based upon further social-cultural experiments, again in line with the spirit of the time. The 1968 destruction of the Pruitt–Igoe urban housing projects designed by Minoru Yamasaki signified a pivotal change in thinking about architecture, away from the anonymous factory, toward more diversified, socially oriented, experimental spatial typologies. This shift was started perhaps with the Yale School of Architecture, designed by Paul Rudolph.

Yale School of Architecture – Paul Rudolph

Finished in 1963, the architect seems to have anticipated the social-cultural change, since instead of clear, flexible open spaces, the building has quite a complex network of smaller, very particular spaces which are connected in labyrinthine ways.

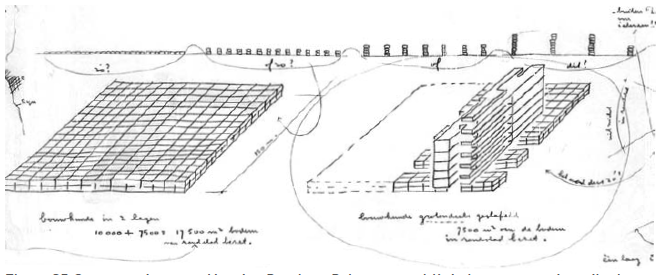

According to Data (2012) the building turns into a story book, as you pass through varying volumes and spaces of different densities which take on different activities. These create private little pockets and small spaces for different programs. The TU Delft School of Architecture’s new building of that time, Bouwkunde by Broek-Bakema (1970), also purposefully tried to break the all-is-possible-box structure. The architects literally divided the several components of an all-encompassing box up into public elements that could be regrouped along a central street and private study spaces into a slab hovering above the street.

TU Delft Bouwkunde – Broek-Bakema

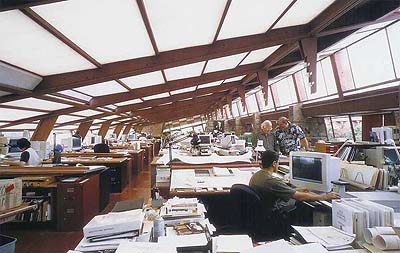

The public elements included the canteen, model shop, drawing studios, etc. and were configured along a central street that resembled an actual outdoor street, with streetlights and informal seating places for exchange and interaction. A similar idea of arranging individual spatial elements along public circulation was used by Frank Lloyd Wright in his Taliesin West School of Architecture, although the architecture expression and site conditions created a very different typology. Wright’s school was grouped almost like a small prairie town, in which the various architectural elements created very diversified internal spaces, and the close connection with the outdoor space enabled a rich inside out dynamic.

Taliesin West – Frank Lloyd Wright

The building thus became part of the landscape, rather than ‘anchored into the ground’ (Renaissance) or ‘lightly poised upon the earth’ (Bauhaus).

This relation of building to landscape was also typologically explored by Aldo van Eyck’s Orphanage, home of the Berlage Institute, in which the building enables the interior spaces to become a continuous learning landscape.

4. Post ’90’s

In the past two to three decades there has been a global increase in the building of new schools of architecture and again a shift in typologies following changing social value systems. Or perhaps we can say that it seems the wide-ranging spatial experiments of the post-60’s have resulted in two dominant typologies; the ‘patchwork ‘and the ‘box-in-box’.

The patchwork type stems from the social-cultural shift following sustainable environmental awareness. The starting point is to re-use and re-generate rather than build new, a trend already expressed by the Berlage Institute in 1990. A part of this re-use strategy is also adding elements to existing buildings that make them suitable for architectural education.

The box-in-box type perhaps finds its origin in an increasingly rapidly changing educational environment, with technology leading a change in the process of building and design, in which future spatial requirements are not clear. The resulting a ‘box-in-box’ typology splits itself between certain and un-certain elements and thus maintaining efficient planning.

Examples of the Patchwork typology typology included TU Delft’s 2008 ‘BK City’, in which the school decided to opt for an extensive, and swiftly executed regeneration of a former university building rather then building a completely new one, following the sudden fire and collapse of the Broek-Bakema designed building mentioned earlier. What is surprising in addition to reusing an existing building, is that school asked a team of architects to come up with a strategy to add end re-use.

Specific architectural education spaces were housed in newly covered courtyards, and the existing structure was to house the more flexible desks, offices and studios.

TU Delft Model Shop – A new covered courtyard between existing buildings.

Cornell University’s School of Architecture extension by OMA follows a similar model, in which one new element, a floating box, radically redefines the existing traditional typology. The new, floating, Milstein Hall connects several much older structures and at the same time adds new spatial typologies to the school.

Milstein Hall at Cornell – OMA

The Strelka Institute in Moscow, Russia uses a more scattered patchwork strategy, similar in spatial arrangement to Frank Lloyd Wrights ‘prairie town idea’, in which loosely placed architectural elements create an almost playground like urban environment that serves both the school and the wider urban context. It thus not only regenerates the existing buildings, but becomes a catalyst for the surrounding exterior area as well.

Lastly, two examples of the ‘box-in’box typology. Firstly, the Marne La Vallee school in Paris, France by Bernard Tschumi. According to the architect, the design of the school

“begins from the thesis that there are ‘building-generators’ of events which (…) accelerate or intensify a cultural and social transformation that is already in progress.”

Spatially this translates to a central space as a social environment that houses the main public programs in sculpted ‘boxes’, surrounded by more ‘private’ components around the atrium’s edge. The second example, Melbourne University’s School of Design (MSD), designed by JWA/ NADAA, follows this same spatial strategy. The design comprises of a central Studio Hall, surrounded by studio and office spaces, with meeting rooms inside a sculptural volume floating in the hall. The Studio Hall itself is a large flexible space that “provides for informal occupation over all times of the day”. Notable in this design is also how the edge of the atrium provides an in habitable buffer between the public and the private spaces.

Melbourne University’s School of Design – JWA/NADAA

Teaching ideology expressed through interior organization

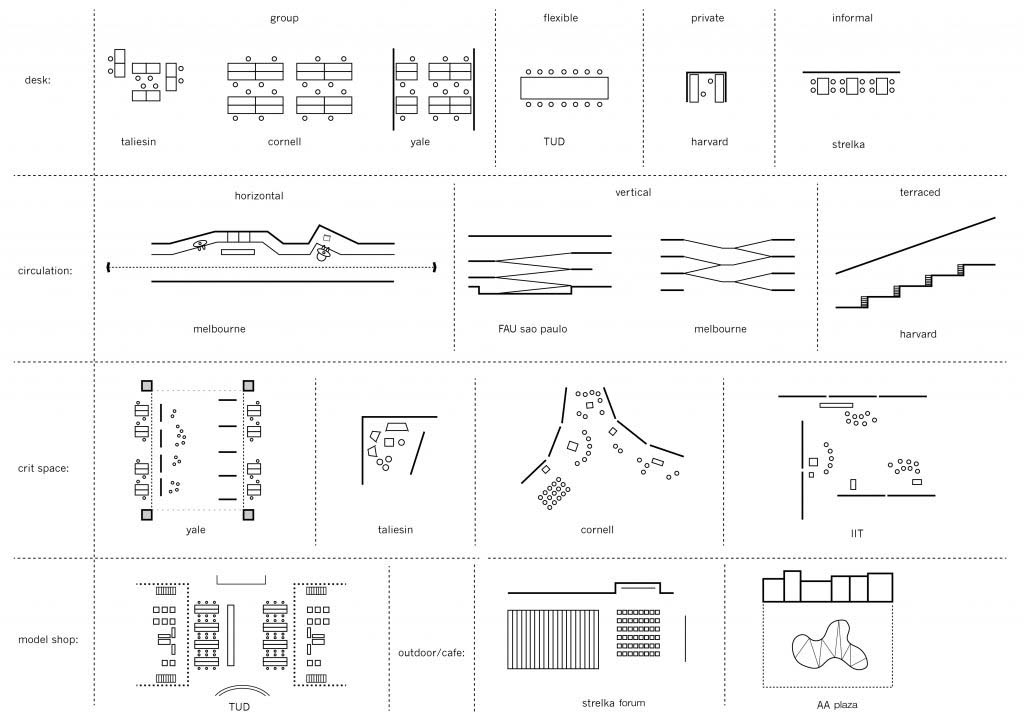

In addition to the architectural typology of the buildings designed for architectural education, the teaching pedagogy is also heavily relying on the interior organization. There are various specific didactic spatial components for architectural education, and these can be designed and interpreted differently according to a prevailing teaching ideology. Below are three basic examples of spatial elements picked from the before-mentioned schools.

1. Student Arrangment

In order to draw, whether it’s on a laptop, fixed computer or sketch tool and paper, a student needs a flat surfaces to work on. This is most often in the form of a desk, which initially seems an arbitrary element in the design of schools, however, the type of desk and its arrangement can heavily influence or communicate the educational ideology. For instance, whether the size of a desk allows for drawing presentation drawings, or building models, or only has room for a laptop determines whether students are encouraged to use a model shop for group work, or instead remain fixed to their own desks.

Gund Hall at Harvard

Or whether the desks are individually placed back to back (eg. Harvard’s Gund Hall), separated, or grouped together in small groups (Yale) or in an open plan office style (Cornell), or perhaps assigned to a person throughout for the duration of the program (eg. Harvard GSD), or flexibly defined on a day to day basis (TU Delft), or informally occupied (Strelka) all influence the teaching possibilities. It determines whether a student is encouraged to interact, or to stay put.

Group work around large tables at BK City, TU Delft

2. Circulation

All schools also need circulation, like they all need desks. In the same way that a desk communicates a philosophy, so does the circulation influence spaces for education of creative disciplines. In particular the circulation between one student, or groups of students. Or the circulation between public parts of the school, like lecture halls or model shops, and private working areas. There are various way the learning system can be expressed in the way the circulation is part of the architectural expression. Perhaps the horizontal circulation becomes a place for informal exchange and meetings (like at the Melbourne School of Design, or the vertical circulation is designed as a connecting, continuous street instead of using elevators (like at Sao Paolo’s FAU). Or, you can use the stacking of elements as a stepped terrace so that students can look out onto each other’s work in progress if they stand up, while still maintaining their individual privacy (Harvard GSD).

3. Crit space

Very specific for architectural education are the ‘crit’ or review spaces, in which students pin up and present their works in front of a design jury. Designs for these reviews broadly fall into two categories; designated review space, or flexible review spaces. In Yale, the crit space is a flexible space conceived as a double height volume in the centre of the floor, called the review hall. It is open from all sides and pours out in the studio spaces with student desks, which can be used for other public activities when there are no reviews taking place.

Crit space at Yale School of Architecture

The studio spaces are actually arranged around this central review space and are connected to the upper mezzanine of studio spaces. These upper spaces become “overlooking, floating slabs which give an opportunity to be together, yet separate; involved yet detached”. In Taliesin however, the review space is very differently situated, not very formal in the centre of the attention, but in a separated section, with sofas and lounge chairs that allow for a more informal presentation environment.

Crit space at Talisien West

Conclusion

This article has tried foremost to find a base to compare the several types of spaces for architectural education, and should not be seen as an in-depth conclusion about the success of their intentions, or a subjective valuation of their appropriation. In fact, though not directly clear from the previous overview, if we compare the discussed cases to the 2017 QS ranking of top hundred schools of architecture in the world, not all the top-ranked Western architectural schools (including MIT, Cambridge or ETH Zurich) have buildings designed specifically for their respective teaching typology. Whether such a link is necessary to foster the quality of education in line with the ideology is thus debatable, as the school of architecture ranked 1st in the ranks, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is housed in a ‘Pantheon style’ building which in its typological conservatism couldn’t be more opposite with their forward oriented teaching philosophy.

Architecture school at MIT

However, of the top ten ranked western schools, most of them have buildings that express, or are made to fit for heir teaching ideology, including TU Delft, Harvard GSD, UC Berkeley, Bartlett. In addition, we can clearly see that within the over-arching typology there is a palette of interior organizational characteristics that in addition to the typology of the architecture express the teaching character of the school.

In his article on the pedagogic aspect of design teaching spaces, Zhang (2017) states that spaces for design teaching have fundamental impacts in the setting up of our values towards architecture. With this paper, the author hopes to have shown that indeed the design of spaces for architectural education can and has been a translation of an idea, or values regarding architectural education.

Bibliography

Akin, Omer. ”Role models in architectural education,” in The Role of the Architect in Society, ed. by P. Burgess, Pittsburgh: Carnegie Mellon University, Department of Architecture, 1983, pp. 9-13.

Collins. Architectural Criteria & French Traditions. 1966

Cret, Paul P. The Ecole Des Beaux-Arts and Architectural Education. Journal of the American Society of Architectural Historians 1, no. 2 (1941): 3-15.

Gropius, Walter. The New Architecture and the Bauhaus. MIT Press. 1965

Hertzberger, Herman. Lessons for Students in Architecture. 010 Publishers. 2001

Johansson, R. Case study methodology. Methodologies in Housing Research, Stockholm. 2003

Lewis, Paul, Tsurumaki, Marc and Lewis, David J. The Manual of Section. Princeton Architectural Press. 2008

Salama, Ashraf. New trends in architectural education: Designing the design studio. Arti-arch, 1995.

Schon, Donald A. Beyond the stable state: Public and private learning in a changing society. Maurice Temple Smith Ltd. 1971

Thompson, Eric D. National Historic Landmark Nomination: S.R. Crown Hall, National Park Service. 2000

Van der Voordt, Theo & Zijlstra, Hielkje & Dobbelsteen, Andy & Dorst, M. Integrale plananalyse van gebouwen. Doel, methoden en analysekader. 2007

Weismehl, Leonard A. Changes in French Architectural Education. Journal of Architectural Education Vol. 21 , Iss. 3,1967

Zhang, Li. Pedagogical Positions of Design Teaching Spaces. World Architecture. 2017. July Issue, pp. 8-9

Web

https://www.beauxartsparis.fr/fr/locations-d-espaces

http://www.tschumi.com/projects/15/#

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berlage_Institute

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Architectural_Association_School_of_Architecture

Koehler, Marc and De Geus, Martijn. Ego-Eco System. 2008. Accessed via: https://www.archined.nl/2009/03/building-for-bouwkunde-the-nominees-the-winners https://arch.iit.edu/about/history

JWA/ NADAA. Melbourne School of Design University of Melbourne. Archdaily. 2015. Accessed via: http://www.archdaily.com/622708/melbourne-school-of-design-university-of-melbourne-john-wardle-architects-nadaaa

http://www.eekhoutbouw.nl/expertise/bedrijfsruimten/tu-delft-bouwkunde-delft/

https://aap.cornell.edu/about/campuses-facilities/ithaca/milstein-hall/studio-overhead

Foster, James. T. Moscow’s Strelka Institute and the HSE Graduate School of Urbanism Launch a New Course in Advanced Urban Design. 2016. Accessed via: http://www.archdaily.com/783143/moscows-strelka-institute-and-the-hse-graduate-school-of-urbanism-create-a-new-course-in-advanced-urban-design

Cour vitrée du Palais des Études où se situait le Musée des Antiques – 1937 Photographie de Georges GliDFARB (Atelier libre d’Architecture EXPERT). Accessed via: http://www.grandemasse.org/?c=actu&p=ENSBA-ENSA_genese_evolution_enseignement_et_lieux_enseignement

Daga, Anuj. The Paul Rudolph Hall. 2012. Accessed via:

architecture school, education, space, teaching